African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement is inching toward the 22-country threshold needed for its implementation.

The African Union envisioned the free trade zone spanning the entire continent — with a combined gross domestic product of at least $2.3 trillion — as a means of improving the movement of goods, services and people among the AU’s 55 members.

By integrating economies and reducing trade barriers such as tariffs, it aims to increase employment prospects, living standards and opportunities for the region’s 1.3 billion people — and to make Africa more globally competitive.

Right now, “intra-African trade only represents 15 percent of total African exports,” said Landry Signe, a proponent of the deal and a scholar with the Washington-based Brookings Institution’s Global Economy and Development Program.

By comparison, 58 percent of Asian trade and 67 percent of European trade remains within those regions, the Cameroon native said.

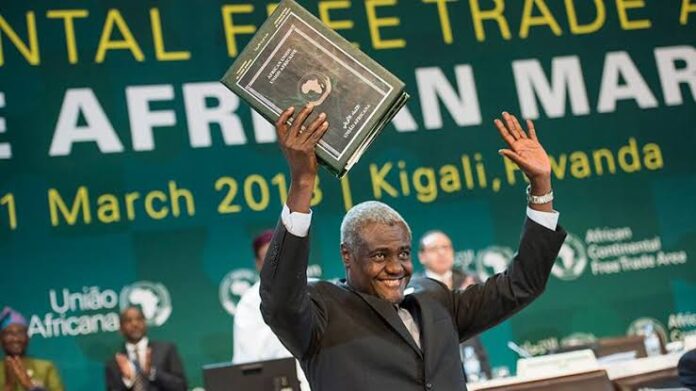

Officials from 44 countries signed the framework establishing the trade pact on March 21, 2018, in Rwanda’s capital, Kigali. Several others have signed since.

Each country’s parliament still must approve the deal, a process that could take years. Nineteen countries have ratified the agreement, leaving it just three short of the minimum before the agreement can take effect.

The latest to ratify, as of February, is Ethiopia, whose reform-minded Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has pushed for business liberalization and increased private investment since taking office last April. The Horn of Africa country, with a fast-growing economy, also has won praise from the International Monetary Fund for a decade of strong development.

While South Africa has already ratified the deal, Nigeria — one of the continent’s other leading economies — has not signed.

“We will not agree to anything that will undermine local manufacturers and entrepreneurs, or that may lead to Nigeria becoming a dumping ground for finished goods,” President Muhammadu Buhari said in a Twitter post after skipping the AU meeting last year.

Nigeria has developed major trade relations with Asia, Eastern Europe and the Gulf region, and “fears potentially adverse trade and wants to know the costs and impacts to its economy,” said Raymond Gilpin, an economist and dean of academic affairs at the Africa Center for Strategic Affairs.

But, with Buhari’s re-election in February and with the prospect of African free trade bringing in more investment and jobs, Gilpin said, “I would be very surprised if Nigeria sits on the sidelines” of the trade pact.

Africa primarily exports raw materials, such as crude oil, precious metals and stones, cocoa and other agricultural products. It largely imports finished goods.

With the trade pact, participating countries would commit to removing tariffs on 90 percent of goods and services. With more sharing of goods, services and information, it could address barriers such as lengthy delays at border crossings.

“Currently, East African countries are trading amongst themselves at only half their potential, and the growing local demand is met by imports from outside the continent rather than by local production,” Andrew Mold, agriculture director for the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, said last March at the pact’s launch.

A commission study projects higher foreign investment, lower prices for consumer goods, expanded economic diversification and accelerated industrial development once the agreement takes effect.

The African Union said the pact would create jobs — vital in sub-Saharan Africa, where 70 percent of the residents are younger than 35. Many are underemployed and living in poverty.

Signe predicted the deal also would give Africans a capacity “to collectively negotiate further when engaging with European partners, North American partners.”

More