For over 25 years, maritime strategy and port development in the Red

Sea and Gulf of Aden appeared relatively static. Eritrea looked inwards,

neglecting its coast. Djibouti flourished, lucratively embracing

Ethiopia’s trade, overseas investors and foreign military bases.

Somalia’s shores became synonymous with piracy, prompting Western and

Asian naval manoeuvres, quietly ensuring free passage to the Suez Canal.

Sea and Gulf of Aden appeared relatively static. Eritrea looked inwards,

neglecting its coast. Djibouti flourished, lucratively embracing

Ethiopia’s trade, overseas investors and foreign military bases.

Somalia’s shores became synonymous with piracy, prompting Western and

Asian naval manoeuvres, quietly ensuring free passage to the Suez Canal.

But now things may be changing. Ports in the Horn of Africa and Gulf of Aden are suddenly in the spotlight.

Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has repeatedly emphasised port

developments on his whistle-stop tour of neighbouring countries,

including Somalia, Sudan and Djibouti. The rapprochement between

Ethiopia and Eritrea raises the possibility that the mothballed Eritrean

ports of Assab and Massawa could be rehabilitated. And just 25km across

the Bab al-Mandab straits, the war in Yemen has given nearby African

ports new geostrategic significance; the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has

been using its base in Eritrea’s port of Assab to besiege and bomb

Yemen’s crucial port of Hodeida since mid-June

developments on his whistle-stop tour of neighbouring countries,

including Somalia, Sudan and Djibouti. The rapprochement between

Ethiopia and Eritrea raises the possibility that the mothballed Eritrean

ports of Assab and Massawa could be rehabilitated. And just 25km across

the Bab al-Mandab straits, the war in Yemen has given nearby African

ports new geostrategic significance; the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has

been using its base in Eritrea’s port of Assab to besiege and bomb

Yemen’s crucial port of Hodeida since mid-June

These developments beg three key questions. Firstly, why are

countries in the Horn of Africa developing so many new ports? Secondly,

who will finance these projects? And finally, how do control of ports in

the Horn relate to the war in Yemen?

countries in the Horn of Africa developing so many new ports? Secondly,

who will finance these projects? And finally, how do control of ports in

the Horn relate to the war in Yemen?

Why so many new ports?

The first question is the most straightforward. The Horn needs

improved ports and infrastructure to handle the current pace of

Ethiopia’s economic growth, on which broader regional integration and

prosperity relies. This is why ports have been one of Prime Minister

Abiy’s priorities on his foreign visits.

improved ports and infrastructure to handle the current pace of

Ethiopia’s economic growth, on which broader regional integration and

prosperity relies. This is why ports have been one of Prime Minister

Abiy’s priorities on his foreign visits.

In Djibouti, he called for joint investment in the tiny nation’s

ports. In Sudan, he and President Omar al-Bashir presented plans to

modernise Port Sudan together. And in Somalia, he announced that

Ethiopia would work with Mogadishu to upgrade four Somali ports.

ports. In Sudan, he and President Omar al-Bashir presented plans to

modernise Port Sudan together. And in Somalia, he announced that

Ethiopia would work with Mogadishu to upgrade four Somali ports.

Land-locked Ethiopia is clearly looking to break its heavy dependence

on Djibouti, which has handled 90% of its foreign trade since the

border war with Eritrea was triggered in 1998. However, it is crucial to

understand that Addis is only seeking to diversify its access to the

sea – and drive-down freight costs via increased competition – rather

than reduce its use of Djibouti. In fact, these trade volumes will

continue to grow as Ethiopian, Chinese and Djiboutian authorities have

invested heavily in upgrading and enhancing infrastructure capacity

along the Djibouti corridor.

on Djibouti, which has handled 90% of its foreign trade since the

border war with Eritrea was triggered in 1998. However, it is crucial to

understand that Addis is only seeking to diversify its access to the

sea – and drive-down freight costs via increased competition – rather

than reduce its use of Djibouti. In fact, these trade volumes will

continue to grow as Ethiopian, Chinese and Djiboutian authorities have

invested heavily in upgrading and enhancing infrastructure capacity

along the Djibouti corridor.

Earlier this year, the centrepiece of this strategy – the 750km

railway linking Addis Ababa to Djibouti – began full operations. The

$3.4 billion project – financed, constructed and managed by China – has

drastically cut the time and cost of shuttling containers between

Ethiopia’s capital, its nascent manufacturing export zones, and

Djibouti’s ports. The development of prospective oil and gas projects in

Ethiopian Ogaden and neighbouring Somali states, which would also be

exported via Djibouti, reaffirms the port nation’s ongoing centrality to

regional growth and integration.

railway linking Addis Ababa to Djibouti – began full operations. The

$3.4 billion project – financed, constructed and managed by China – has

drastically cut the time and cost of shuttling containers between

Ethiopia’s capital, its nascent manufacturing export zones, and

Djibouti’s ports. The development of prospective oil and gas projects in

Ethiopian Ogaden and neighbouring Somali states, which would also be

exported via Djibouti, reaffirms the port nation’s ongoing centrality to

regional growth and integration.

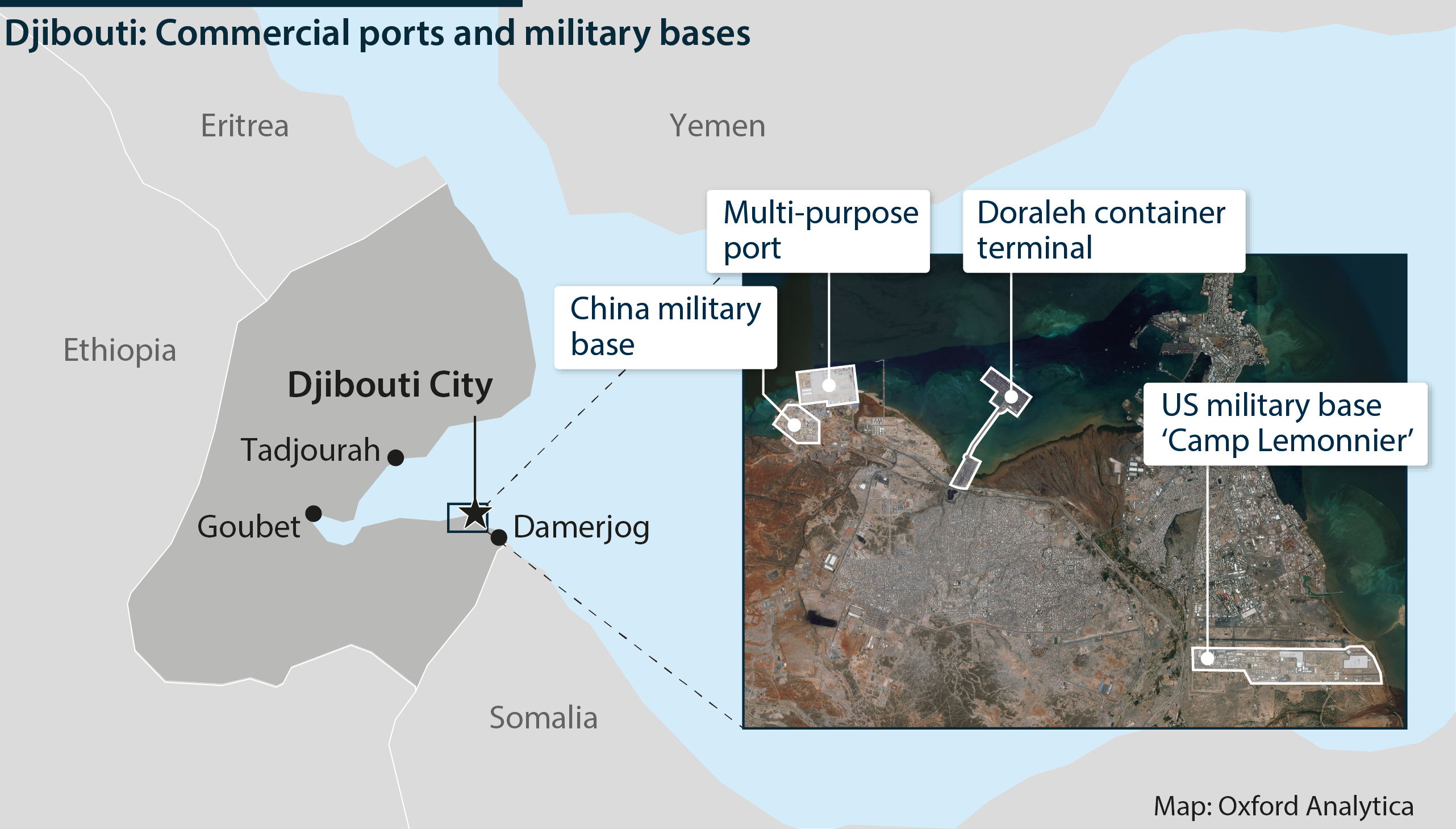

This relationship is as crucial to Djibouti as it is to Ethiopia.

Port transit fees are the mainstay of Djibouti’s exchequer and it has

invested substantially in further developing this infrastructure. It

constructed vast new container and cargo facilities in the form of the

$590 million Multi-Purpose Port (MPP) at Doraleh. Meanwhile, it has

begun developing smaller ports too. Tadjourah, is designed to handle

Ethiopia’s potash; Damerjog will have facilities to export livestock and

liquid natural gas (LNG).

Port transit fees are the mainstay of Djibouti’s exchequer and it has

invested substantially in further developing this infrastructure. It

constructed vast new container and cargo facilities in the form of the

$590 million Multi-Purpose Port (MPP) at Doraleh. Meanwhile, it has

begun developing smaller ports too. Tadjourah, is designed to handle

Ethiopia’s potash; Damerjog will have facilities to export livestock and

liquid natural gas (LNG).

Djibouti’s ambitious “Vision 2035”

blueprint for national development sees its harbours as a hub for Asian

transhipments, servicing the entire region. As it develops ports and

extensive Free Trade Zones

with its Chinese partners, the entrepôt nation will remain critical for

Ethiopia and prospects of regional economic integration, irrespective

of developments in Eritrea or Somalia. It also seeks to maintain its

competitively vis-à-vis Kenya’s LAPSSET corridor, which aims to link its coast at Lamu to South Sudan and Ethiopia.

blueprint for national development sees its harbours as a hub for Asian

transhipments, servicing the entire region. As it develops ports and

extensive Free Trade Zones

with its Chinese partners, the entrepôt nation will remain critical for

Ethiopia and prospects of regional economic integration, irrespective

of developments in Eritrea or Somalia. It also seeks to maintain its

competitively vis-à-vis Kenya’s LAPSSET corridor, which aims to link its coast at Lamu to South Sudan and Ethiopia.

Who’s paying?

The second question this raises is who is paying for all this.

For Ethiopia and Djibouti, the key actor is China.

Djibouti’s major infrastructure initiatives are being financed and

spearheaded by Chinese companies. Djibouti’s new multi-million MPP

facility at Doraleh, for example, is managed and part-owned by China

Merchants Group (CMG). Since 2013, the Hong Kong-based conglomerate has

owned 23.5% of Djibouti’s Port and Free Zone Authority (DPFZA) and, in early 2017, bought a minority stake in Ethiopia’s state-owned shipping line, whose home port is Djibouti.

spearheaded by Chinese companies. Djibouti’s new multi-million MPP

facility at Doraleh, for example, is managed and part-owned by China

Merchants Group (CMG). Since 2013, the Hong Kong-based conglomerate has

owned 23.5% of Djibouti’s Port and Free Zone Authority (DPFZA) and, in early 2017, bought a minority stake in Ethiopia’s state-owned shipping line, whose home port is Djibouti.

CMG is a leading commercial actor in numerous ports along China’s

Maritime Silk Road, which links shipping lanes along Beijing’s global

Belt and Road Initiative. As Thierry Pairault

has highlighted, CMG’s role in Djibouti mirrors Chinese involvement in

ports and logistics elsewhere in Africa. However, Djibouti is unique in

two ways: firstly, it is a telecommunications hub where several key

transcontinental submarine fibre-optic cables meet; and secondly, it has

been home to China’s first permanent overseas naval base since 2017,

when it opened next to the MPP, barely 12km from the US AFRICOM base at

Camp Lemonnier.

Maritime Silk Road, which links shipping lanes along Beijing’s global

Belt and Road Initiative. As Thierry Pairault

has highlighted, CMG’s role in Djibouti mirrors Chinese involvement in

ports and logistics elsewhere in Africa. However, Djibouti is unique in

two ways: firstly, it is a telecommunications hub where several key

transcontinental submarine fibre-optic cables meet; and secondly, it has

been home to China’s first permanent overseas naval base since 2017,

when it opened next to the MPP, barely 12km from the US AFRICOM base at

Camp Lemonnier.

Chinese companies also have significant stakes in Ethiopia’s oil and

gas fields in the Ogaden region. In November 2017, they agreed to

construct a 650km oil pipeline to Djibouti and proposed building a LNG refinery at Damerjog.

gas fields in the Ogaden region. In November 2017, they agreed to

construct a 650km oil pipeline to Djibouti and proposed building a LNG refinery at Damerjog.

The other key actor is the UAE.

Until the opening of the China-run MPP in Djibouti last year, all of

Ethiopia’s container traffic was channelled through the adjacent Doraleh Container Terminal

(DCT). This facility had been managed and part-owned by the Dubai-based

company DP World since 2008, but this February, Djibouti unilaterally

terminated its contract and nationalised its 33% shareholding. This was

the culmination of a fractious six-year legal battle.

Ethiopia’s container traffic was channelled through the adjacent Doraleh Container Terminal

(DCT). This facility had been managed and part-owned by the Dubai-based

company DP World since 2008, but this February, Djibouti unilaterally

terminated its contract and nationalised its 33% shareholding. This was

the culmination of a fractious six-year legal battle.

DP World is seeking compensation for its lost assets, and until the

case is resolved in a London court, the Djiboutian government will have

difficulty selling the sequestered shares legally. However, given Abiy’s

surprise proposal that Ethiopia and Djibouti hold stakes in each

other’s ports and telecommunications, it is possible that Ethiopia may

obtain a minority shareholding in Doraleh Container Terminal. This could

plausibly be part of a deal involving Chinese loans that could also see

CMG gain a bigger slice of DPFZA equity.

case is resolved in a London court, the Djiboutian government will have

difficulty selling the sequestered shares legally. However, given Abiy’s

surprise proposal that Ethiopia and Djibouti hold stakes in each

other’s ports and telecommunications, it is possible that Ethiopia may

obtain a minority shareholding in Doraleh Container Terminal. This could

plausibly be part of a deal involving Chinese loans that could also see

CMG gain a bigger slice of DPFZA equity.

While this spat has seen UAE’s long-standing involvement in Djibouti

diminish, DP World is simultaneously increasing its footprint in

neighbouring ports. In May 2016, the company signed a 30-year deal worth

$440 million to develop Berbera port in the self-declared state of

Somaliland. In March 2018, DP World scaled back its proposed investment,

but announced that Ethiopia would take a 19% stake in the project,

alongside its own 51% share and the Somaliland government’s 30%.

diminish, DP World is simultaneously increasing its footprint in

neighbouring ports. In May 2016, the company signed a 30-year deal worth

$440 million to develop Berbera port in the self-declared state of

Somaliland. In March 2018, DP World scaled back its proposed investment,

but announced that Ethiopia would take a 19% stake in the project,

alongside its own 51% share and the Somaliland government’s 30%.

The company is also investing in building a highway to link the port

to Ethiopia’s border. Meanwhile, the deal has allowed the UAE, which is

playing an increasingly central role in the war in Yemen, to develop a

naval base alongside Berbera.

to Ethiopia’s border. Meanwhile, the deal has allowed the UAE, which is

playing an increasingly central role in the war in Yemen, to develop a

naval base alongside Berbera.

The DP World deal is the first large international contract signed by

the autonomous government of Somaliland. This has angered the Federal

Government of Somalia, which doesn’t recognise the Somaliland

government’s sovereignty over Berbera. This has, in turn, fuelled a spat between Somalia and the UAE,

leading the latter to withdraw military supplies and advisors and close

the hospital it was funding in Mogadishu. The row also compounded

allegations that the Somali government is being manipulated by Qatar and

its ally Turkey. Qatar reportedly helped finance President Mohamed

“Farmaajo’s” election campaign, while Turkey is the Somali government’s

leading economic partner.

the autonomous government of Somaliland. This has angered the Federal

Government of Somalia, which doesn’t recognise the Somaliland

government’s sovereignty over Berbera. This has, in turn, fuelled a spat between Somalia and the UAE,

leading the latter to withdraw military supplies and advisors and close

the hospital it was funding in Mogadishu. The row also compounded

allegations that the Somali government is being manipulated by Qatar and

its ally Turkey. Qatar reportedly helped finance President Mohamed

“Farmaajo’s” election campaign, while Turkey is the Somali government’s

leading economic partner.

What are the UAE’s plans for Yemen and the Horn?

The fact that the UAE’s involvement in Berbera has enabled it to set

up a naval base there leads us to our third question: how is competition

over new container and cargo ports linked to the war in Yemen?

up a naval base there leads us to our third question: how is competition

over new container and cargo ports linked to the war in Yemen?

This is the most difficult to answer, but it is clear that as the

UAE’s prosecution of the war against the Houthis has intensified, so has

their engagement in the Horn of Africa. Since 2015, the UAE has massed

military and naval hardware alongside covert training and detention

facilities in the Eritrean port of Assab. Its armed forces are also now

present in Berbera in Somaliland (as well as on Socotra island and Yemen’s southern coast).

UAE’s prosecution of the war against the Houthis has intensified, so has

their engagement in the Horn of Africa. Since 2015, the UAE has massed

military and naval hardware alongside covert training and detention

facilities in the Eritrean port of Assab. Its armed forces are also now

present in Berbera in Somaliland (as well as on Socotra island and Yemen’s southern coast).

Is the war in Yemen also the reason that UAE authorities now appear

to be investing energetically in diplomatic overtures to both Ethiopia

and Eritrea? In May, Prime Minister Abiy visited the UAE. In June, Crown

Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi (MBZ) returned

the favour. During this visit, the UAE’s de facto ruler

announced a $1 billion emergency loan to ease Ethiopia’s acute forex

shortage and promised further foreign direct investment.

to be investing energetically in diplomatic overtures to both Ethiopia

and Eritrea? In May, Prime Minister Abiy visited the UAE. In June, Crown

Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi (MBZ) returned

the favour. During this visit, the UAE’s de facto ruler

announced a $1 billion emergency loan to ease Ethiopia’s acute forex

shortage and promised further foreign direct investment.

It was then an Emirates plane that ferried the Eritrean delegation to

Addis on 26 June. Furthermore, Eritrea’s President Isaias Afewerki was

subsequently welcomed to Abu Dhabi prior to Abiy’s arrival and effusive

proclamation of peace in Asmara on 8 July.

Addis on 26 June. Furthermore, Eritrea’s President Isaias Afewerki was

subsequently welcomed to Abu Dhabi prior to Abiy’s arrival and effusive

proclamation of peace in Asmara on 8 July.

There are also recent hints from Saudi Arabia and UAE suggesting they

may back Ethio-Eritrean rapprochement with substantial funds. Some

analysts claim these would be used firstly to rehabilitate Eritrea’s

ports of Assab and Massawa. They would then help finance infrastructure

linking Assab to Addis Ababa and, far more ambitiously, Massawa to

Mekelle, the capital of Ethiopia’s Tigray region.

may back Ethio-Eritrean rapprochement with substantial funds. Some

analysts claim these would be used firstly to rehabilitate Eritrea’s

ports of Assab and Massawa. They would then help finance infrastructure

linking Assab to Addis Ababa and, far more ambitiously, Massawa to

Mekelle, the capital of Ethiopia’s Tigray region.

This may be wishful thinking and/or hubris. Nevertheless, Ethiopia

has ambitious, fully-costed long-term infrastructure plans, involving

rail, road, air, and sea routes. Encouraging rival Arab and Chinese

investors to compete for a share of the profits generated by integrating

Eritrea’s ports back into Addis’s long-term infrastructure plans should

be relatively straightforward. However, it is far less certain whether

Eritrea’s dilapidated authorities can undertake domestic economic

reforms and facilitate competitive tendering for new port and maritime

services while fulfilling short-term pledges to the UAE.

has ambitious, fully-costed long-term infrastructure plans, involving

rail, road, air, and sea routes. Encouraging rival Arab and Chinese

investors to compete for a share of the profits generated by integrating

Eritrea’s ports back into Addis’s long-term infrastructure plans should

be relatively straightforward. However, it is far less certain whether

Eritrea’s dilapidated authorities can undertake domestic economic

reforms and facilitate competitive tendering for new port and maritime

services while fulfilling short-term pledges to the UAE.

It is unclear how realistic the suggestion of Arab finance behind the

peace-deal is. It is also impossible to tell whether the UAE’s recent

diplomatic activism reflects a medium-term political strategy or whether

it is simply an opportunistic response to changes in the Horn and a

tactical stop-gap in the bloody stalemate in Yemen.

peace-deal is. It is also impossible to tell whether the UAE’s recent

diplomatic activism reflects a medium-term political strategy or whether

it is simply an opportunistic response to changes in the Horn and a

tactical stop-gap in the bloody stalemate in Yemen.

Does the UAE have a concerted plan in the Horn of Africa? Does it

foresee that its military lease of Assab could be transferred to DP

World once Yemen’s Houthis have been bombarded or starved into

submission?

foresee that its military lease of Assab could be transferred to DP

World once Yemen’s Houthis have been bombarded or starved into

submission?

It is too early to tell, but what is clear is that the ports in the

Horn of Africa are proving to be of increasing interest to rival Arab

and Chinese investors and that the politics of ports have become central

in shaping political alliances and enmities across the region.

Horn of Africa are proving to be of increasing interest to rival Arab

and Chinese investors and that the politics of ports have become central

in shaping political alliances and enmities across the region.